BLOOD ROADS – Nazi forced labour in northern Norway

Dr Marina Panikar

The Nazi camps in Northern Norway for Soviet prisoners of war and their living conditions there

On February 26, 1940, the “considerations for political and administrative measures on the occupation of Norway, Denmark and Sweden” were made public by the OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht; High Command of the Armed Forces). In them the guidelines for the occupation of the northern states were laid out, in which Norway played a crucial role. In the document it states that first and foremost, German military bases should be created, namely in Oslo, Arendale, Kristiansand, Stavanger, Bergen, Trondheim, Narvik and Åndalsnes.

Also mentioned is the great importance of the work on the railway lines Oslo – Lillehammer – Trondheim and Narvik – Riksgränsen – Luleå. The creation of transportation links was above all tied to the Nazi plans to use the raw materials of the country in the interests of the economy of the Reich and to establish in Scandinavia a powerful military toehold.

When in April 1940 Operation “Weserübung” was concluded and Norway and Denmark were under the occupation of Nazi troops, the question arose for the High Command as to where they would find the required work force for the realisation of the established plans. The particular need for a reservoir of labourers in Norway was the grounds for the widespread system of camps for prisoners of war and “Eastern workers”.

Already in April 1940 an order was issued by the OKW for the transfer of 20.000 Soviet prisoners of war to Norway. On arrival in Norway the Soviet prisoners of war were distributed to three base camps – Stalags (Stammlager) as distribution points for the transport of the prisoners to the work camps. Each Stalag was responsible for the camps that were under the jurisdiction of a particular territory to them.

The administrative system of Stalags and battalions in the Norwegian territory

The Nazi system of prisoner of war camps in Norway, headed by General Major Klemm, consisted of Stalags with camps for prisoners of war (22.893 men), air force and construction battalions for prisoners of war (6.188 men), construction battalions (5.204 men), work battalions (35.986 men) and supply battalions (1.095 men). The Soviet prisoners of war transferred to Norway were chosen according to the following principles – their physical condition and ability to carry out different types of work, and some of them also for their professional qualifications, as was also the case in other occupied territories.

In general the Soviet prisoners of war came to Norway through German territory. All transports there went from the German harbour Stettin. The Wehrmacht Command had prepared special instructions for the transport of the Soviet prisoners of war, under which the prisoners were to be transferred on transport ships, each carrying 800 men. On arrival in Norway they would then be taken with specific trains to one of the three Stalag bases.

The first Soviet prisoners of war came to the Norwegian territory in August 1941. On November 9, 1941, there were already 2.847 men. As is evident from Table 5 they were primarily brought to Northern Norway, the most dangerous part of the country at this time, where as is known British-Soviet forces were carrying out extensive operations.

In the documents of the German command in Norway, it is noted that 21 prisoner of war camps formed the structure of the (original) four Stalag bases. Alongside the Soviets, there were also Serb, Yugoslav, Polish, and prisoners from other countries, however 93-95 % of all of the prisoners of war were Soviets.

The majority of all of the prisoners of war were concentrated in the northern county of Nordland, where work for the construction of railway connections was carried out.

In December 1945 it was calculated that 14.902 Soviet prisoners had perished in the country.

On the basis of the available material studied, it can be accepted with great certainty that in the course of the Second World War the number of Soviet citizens in the Norwegian territory amounted to approximately 100.800, and around 91.800 of them were prisoners of war and 9.000 Eastern workers.

Conditions for the handling of the prisoners of war

In the documents of the German command in Norway, the author found a so-called information sheet with instructions for camps under the control of Stalag 303. In this document it is repeatedly pointed out that the prisoners of war should be handled in such a way that their labour force survives and “achieves its maximum work productivity.” Directives of this sort underline once again the intended goal of bringing the prisoners of war to Norway – to exploit them as labourers.

There were different camps – with regard to the demands and the number of camp prisoners – with anywhere from a few hundred to more than ten thousand men.

There were no camp buildings erected in advance, so the prisoners of war would be housed in barracks, run-down buildings or barns.

According to the instructions the camp had to be at an easily manageable location in order to ensure the guarding of it. As a rule the site was surrounded by two rows of barbed wire fence, 2,5 metres high, with space above the ground of no more than 50 centimetres. And in accordance with the instructions a distance of two metres generally separated the rows of barbed wire fencing. Furthermore the outside of the camp was to be well lit.

The internal camp inventory was likewise determined by regulations. The cots in the barracks were ordered one above the other in three rows. When embarking from Germany every prisoner of war was to receive a sort of kit for the duration of the transport and the stay in camp, which included a blanket, a hand towel, a cup and a spoon. Apparently, through this, the German command sought to prevent the spread of infectious diseases and epidemics. The sleeping places were to be outfitted with straw mattresses and old blankets, however they were often missing. This meant that the prisoners of war slept directly on the straw or on the bare floor.

It can be assumed that a certain hierarchy prevailed among the prisoners of war, as was also characteristic of the concentration camps – assistants, helpers of the camp administration, the so-called camp prominence, couriers, police and so on. Of the total number of prisoners, 5-10 % were in this privileged class.

It is difficult to tell to what degree this was representative of the Nazi camps in Norway. It is confirmed in the German information sheet that the prisoners of war themselves were frequently to be camp guards, who “work together with the Germans of their own free will” for an additional ration and better living conditions.

It is specified in German documents that the camps were to be heated in such a way that the prisoners of war would be kept warm and their clothing could dry. The “Commission”, however, established that the camp buildings were poorly heated or not at all, which led to many cases of frostbite in the barracks.

According to the German “Commission”, good clothing and footwear were taken from the prisoners of war. Despite the freezing temperatures, many of them had no outerwear garments. They generally had no socks, no mittens and undergarments and did not receive the appropriate clothing for their hard work. There was no protection from the rain or the cold for them, which particularly in wintertime further intensified the working conditions.

Alongside the unsatisfactory housing conditions for the prisoners of war in the Nazi camps in Norway, the miserable food rations were the main reason for the death rate among them. It was of the greatest importance for the labourers to rely upon themselves to sustain their ability to work. Kitchens and eating areas were lacking in many camps, especially in Northern Norway. The prisoners of war prepared their own meals themselves on an open fire, and used tin cans and pails for this.

The daily ration for the Soviet prisoners of war in Norway consisted of a litre of vegetable soup, 300 grams of bread, and sometimes a bit of meat, potatoes or fish. This is also confirmed by the memories of a former prisoner of war. “We got to eat three times, in the morning cold tea, at midday, soup with rotten vegetables and turnips – both the prisoners as well as the Germans called it barbed wire soup – a bit of bread and tea in the evening, 200 grams of margarine divided between 20 people.” In calories this was about 40-60 % less than a person needs to perform the hard physical work.

This supply situation gives a good idea of the state of health of the prisoners of war. The doctors in the camps were usually prisoners. Tuberculosis, influenza, protein and vitamin deficiency were the main illnesses and the reasons for the death rate of the prisoners in the Nazi camps in Norway. This list of illnesses shows, alongside the insufficient food rations, the harsh climate of the northern regions of the country also had a significant impact on the state of health of the prisoners. The majority of the prisoners were located there.

At the same time, in the “information sheet” in Norway, special attention was placed on the hygienic situation that should prevail in the housing of the prisoners of war.

In a December 30, 1943 letter of Major L. Kreiberg, who was responsible for the repatriation of prisoners of war from Nordland county to London, it states that the situation in Norway with regard to epidemics was extremely problematic – alongside widespread occurrences of lice, there were many tuberculosis afflictions and dysentery, and in the Kirkenes region around 2.300 cases of paratyphoid and infectious diseases that were not known of there before the occupation. However, whether such epidemics would lead to a large-scale loss of prisoners in the camps in Norway is not mentioned.

The sickness rate in many camps in Norway remained very high until the end of the war. So on the day of liberation in camp Oppdal, of the 964 prisoners of war, 360 were sick and bedridden, in camp Nes 90 % were sick.

Another cause of death among the Soviet prisoners of war, alongside hunger and disease, was the brutal handling of them by the guards.

As the Stalag 303 information sheet states, “Since the Soviet prisoners of war are considered enemies, the handling of them must be characterised by particular severity and vigilance.”

On September 6, 1941, an order was issued from the German command in Norway about conduct toward the Soviet prisoners of war. Pointed out in the document is the ban on contact with the prisoners of war and the passing on of correspondence to them. There were boards in the camp with inscriptions in the Russian language such as “Halt. Go further and you will be shot.” By escape attempts the guards had the right to make use of their firearm.

In regard to his position, the guard had to be able to use his firearm at any time. It was forbidden for him to turn his back to the prisoners. For the guarding control one soldier was calculated for ten prisoners. Action was immediately taken against any refusal to work or protest. The camps were guarded around the clock. The guard posts were situated along the entire outer perimeter of the camps. Twice a day – morning and evening – the prisoners had to line up for inspection.

It was categorically forbidden for them to make contact with the local residents or to receive any help from them. For an attempt to get something to eat, they would be thrashed with rifles and could be shot for it. Refusals to work and escape attempts were punished by execution. From the first day of the detention of the prisoners of war in Norway, the German authorities undertook strict measures so as to prevent the local population from coming into contact with the camp prisoners. Harsh punishments were enforced so as to intimidate the inhabitants and prevent them making contact with the Soviet prisoners of war.

As a rule the camps for Soviet prisoners of war were found on the outskirts of populated places and not far from a road. Thus it was possible for the local people to leave packages with food at the edge of the road or at the camp fence.

In addition to helping with provisions of food, the Norwegians also hid escaped prisoners of war, even though they knew that they would face death for being involved with attempts at escape. The local people helped the prisoners with clothing and food items and smuggled them into the ranks of the Hjemmefront, the Norwegian resistance organisation.

In Norway there was an entire unit of escaped Soviet prisoners of war from the camps. They organised hiding places, diversions and acts of sabotage.

The exploitation of the labour of Soviet prisoners of war in Norway

The main goal of the German command relating to the Soviet prisoners of war was the forced exploitation of the labourers for the interests of the Wehrmacht. The State Commission for Norway was the organ responsible for the utilisation of the labour force of the prisoners within the territory of the country. In the technical and traffic division, headed by Dr. Klein, plans were worked out pertaining to the direction, extent and results of the work of the prisoners on the various construction projects. To some extent the Organisation Todt served similar functions.

Under the wartime conditions of the Third Reich in Norway two construction projects had paramount importance: the “Nordland railway” by which the transport of metals, primarily nickel, was to be carried out for German industry and the marine base at Trondheim, the most important point from which to disable the allied naval forces of the anti-Hitler coalition.

In an announcement from the Ministry of Labour of the OKW in Berlin the important occupations were cited, which were crucial for the maintenance of the economy of the Reich: miners, metal and construction workers, locksmiths, transport workers and shoemakers too. Prisoners of war with these occupations were also called for in Norway. The construction of coastal fortifications, roads, and railway lines, extraction of mineral resources, and work in the harbours were the principal fields of activity of the prisoners of war in Norway.

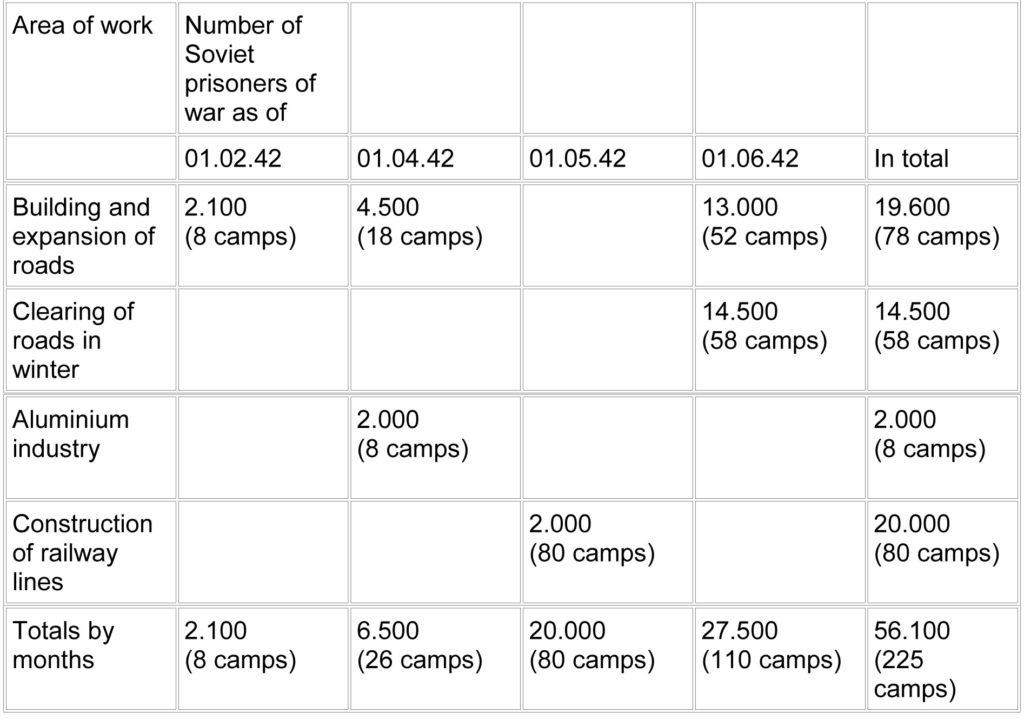

The areas of work of Soviet prisoners of war in the occupied territory of Norway

In the protocol of the Commission it states that Soviet persons were to be used for the execution of the most difficult work. In general the work was done by hand without equipment or tools.

As regards the length of a workday, it conformed to no standard and was different everywhere. On average it ranged from 10 to 14 hours in the various camps, which means about 12 hours.

With respect to the deployment of the Soviet prisoners of war, the construction of roads in Norway had the highest priority. In the labour and construction battalions the prisoners of war were used for the construction of new roads, for the repair, improvement and widening of old roads, for the clearing of snow, for the construction of railway lines and underground routes to the bases and camps. In 1942, twelve large road-building projects can be counted on which the prisoners of war worked.

One of the most important projects was the construction of the Nordland railway, that was needed to connect Mo i Rana with Kirkenes. It was to serve for the transport of military and equipment, as well as metals, which would be conveyed to Northern Norway. Furthermore, in the case of a breakthrough of the German forces in the northern territories, this line would be used for an invasion of the Soviet Union, because the boundaries of the northern countries met there.

The Organisation Todt, which competed with the Reich Commission, succeeded with the cheapest tender, to receive the right to build the Nordland railway. Therefore they were responsible as of 1942 for the execution of the construction work.

The Nordland railway can be divided into two sections of railway lines, the northern and the southern. Both are located in the county of Nordland. In the northern part of the construction project from Fauske to Drag (about 130 km), there were 23 camps with 9.361 Soviet prisoners of war. In the southern Fauske – Mo section, there were also a few dozen camps in which prisoners of war were engaged in the building of the railway.

Altogether, up to the beginning of 1945, 20.432 Soviet prisoners of war from 67 work camps had worked on the Nordland railway. This was approximately 26 % of their total number in Norway. We know that in these territories there was a high death rate among the prisoners. It is therefore to be surmised that the working conditions for the prisoners of war were particularly harsh.

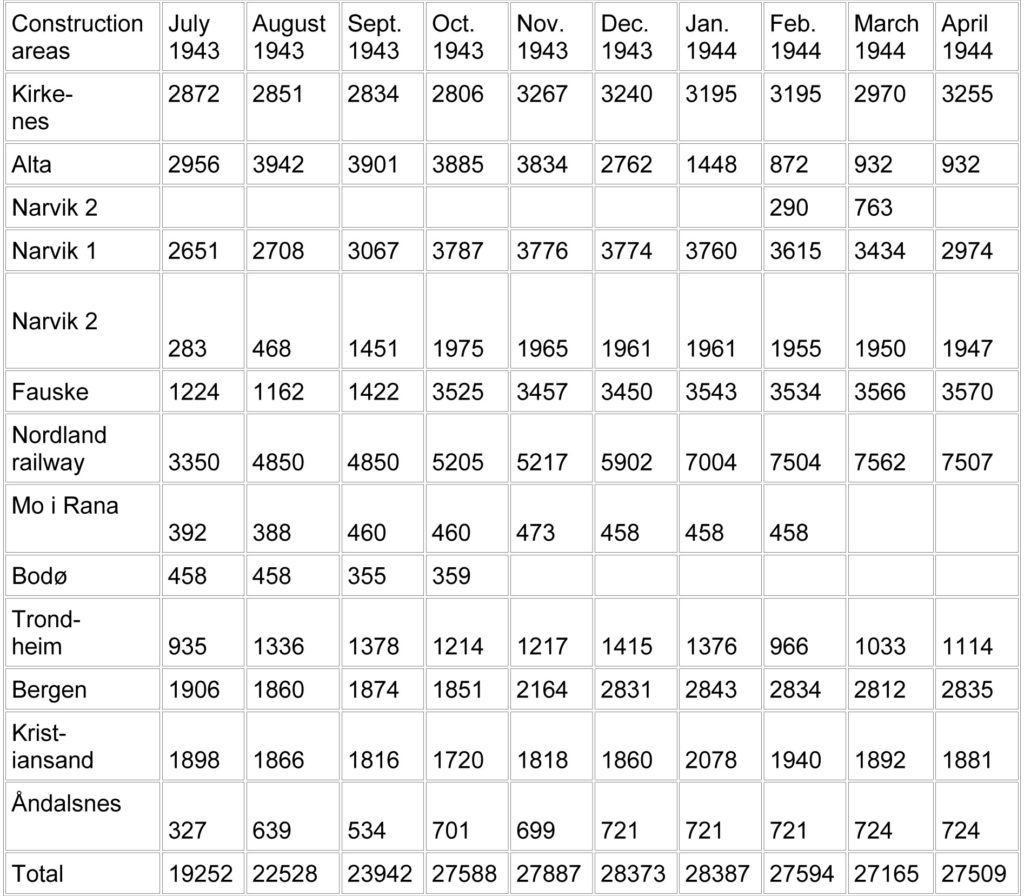

The number of Soviet prisoners of war in the construction areas in Norway from July 1943 to April 1944

For the ten months in which the Soviet prisoners of war were under the responsibility of the Oganisation Todt their numbers increased to 8.527 persons. This shows the great magnitude of the construction activities of the organisation in Norway, and the extensive use of these labourers. The table vividly reflects the increase in the number of prisoners of war that were used in Narvik, Fauske, Bergen, and for the construction of the Nordland railway. The significance of these construction projects is also discussed in the “thoughts on the political and administrative measures for the occupation of Norway, Denmark and Sweden”. The documents of the Organisation Todt are definitive proof that prisoners of war and Eastern workers constituted the main labour force, of which the greatest number were Soviet citizens.